Advertisement

Robin Lutz’s visually compelling, inventive M.C. Escher: Journey to Infinity strikes just the right note of whimsy in exploring the graphic art of a talent known for his sense of the whimsical. Just as his compatriots Bosch, Rembrandt, Vermeer and Van Gogh, created new ways of seeing with, respectively, surrealistic symbolism, chiaroscuro, photorealist style and Post-Impressionism, the Dutch Escher expanded the sense of perception on the flat “limited plane” of paper he imprinted with his unique “visualization of infinity.”

Escher called this sensibility “expressing endlessness” and stated: “I’m not an artist… I’m a mathematician.” The Dutchman’s thoughts and theories have been culled from his letters, diaries and notes. They are read aloud with panache by the English actor Stephen Fry (he has appeared in many mostly British films, such as 1992’s Peter’s Friends), who provides playful, lively, witty narration that sounds, in a good sense, like a performance.

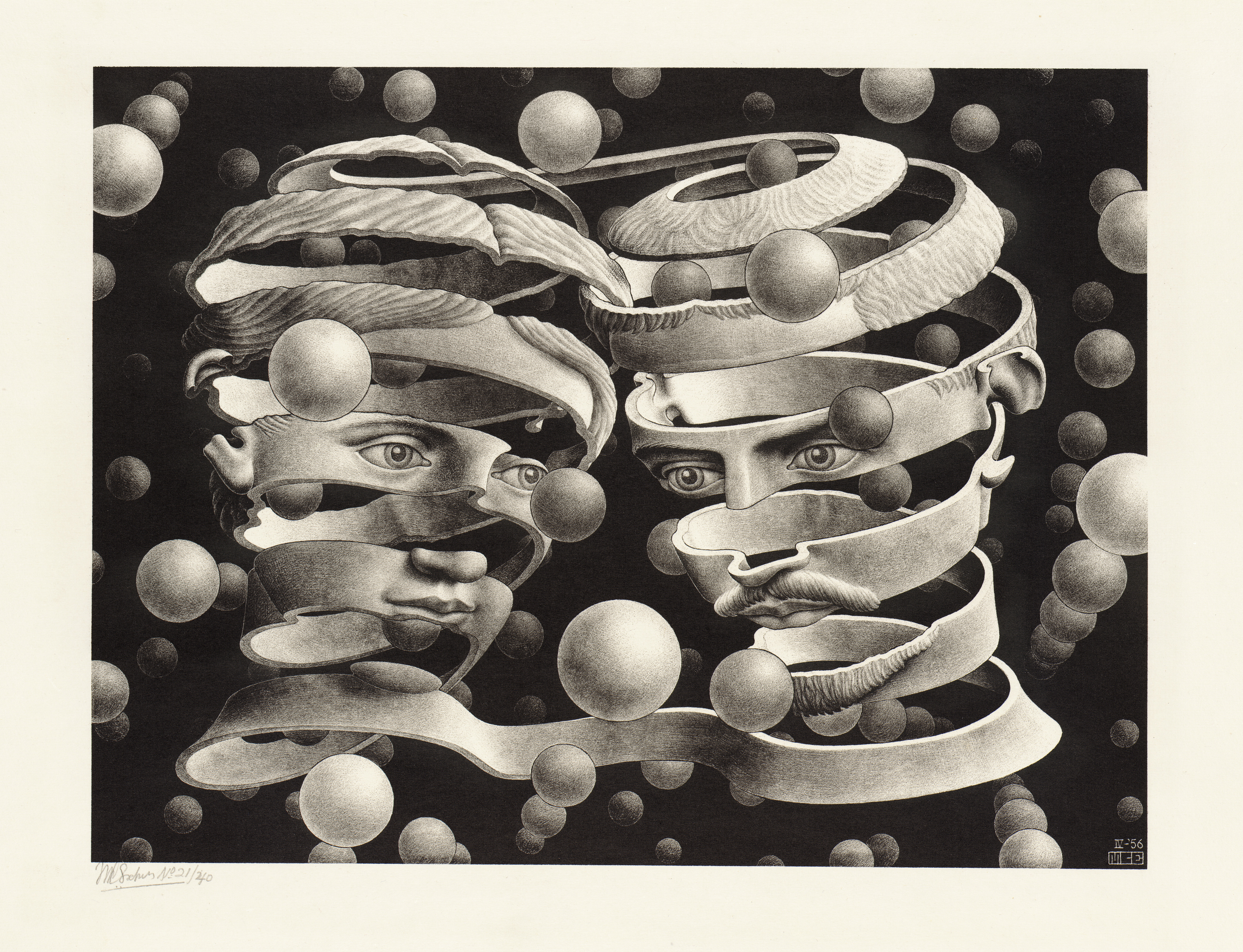

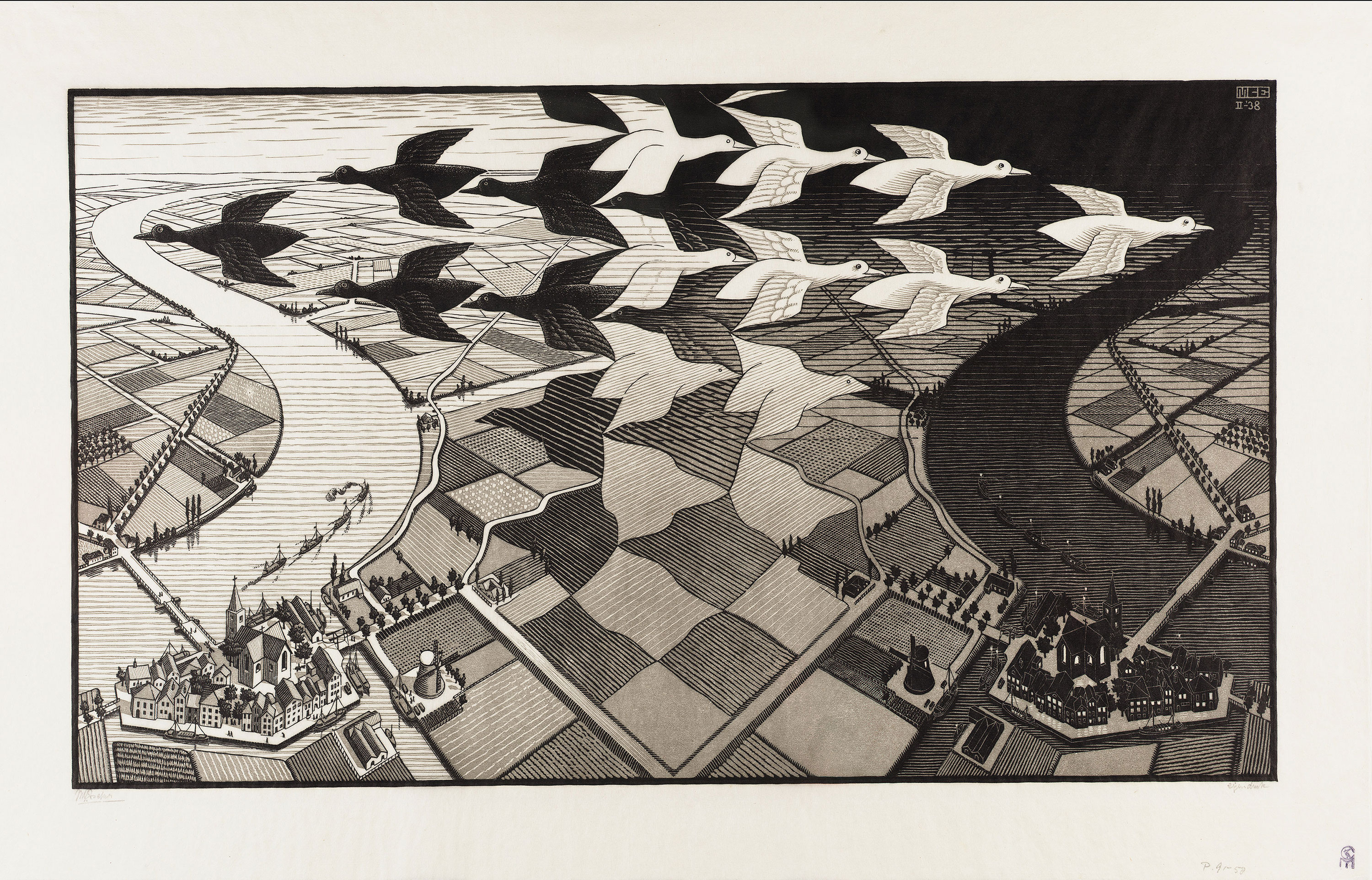

Lutz’s nonfiction biopic, which is in English and Dutch, with English subtitles, creatively renders the life story of Escher and also deftly delves into his sketches, woodcuts and lithographs. The film cuts from cinematography of subjects that inspired Escher to his renderings of them in etchings, etc., which is quite absorbing. Interview subjects include Escher’s sons and daughter-in-law, a geometry expert and, of all people, guitarist Graham Nash (more regarding him later). Journey also includes imaginative animation sequences, clips from various movies featuring (then-)Ellen Page, Ben Stiller and David Bowie, plus an exquisite, eye-popping if all-too-brief montage during the grand finale.

Escher’s journey took him from Holland to Italy, where Escher met the Russian refugee woman (who’d fled the Bolsheviks) he wed. The film has some interesting commentary on (plus archival footage of) Mussolini – Escher left Rome, “So I wouldn’t grow up to be a fascist,” as a son puts it in an onscreen interview.

Putting his prodigious gifts to work, Escher connived passage for himself and his family aboard a ship crossing the Mediterranean in exchange for artwork of the voyage to be used for promotional purposes. While sailing from port to port, “I drew like a maniac. Delightful!” he noted in between landfalls. When he beheld the Alhambra at Granada, Spain, the intricate patterns of the Islamic artwork in tiles and mosaics on walls and floors, with their Moorish “motifs repeat[ing] themselves according to a certain system,” had a profound influence on Escher.

The artist described the effect the Alhambra had on him as triggering his “first attempt to systematize.” This abstract tessellation galvanized Escher’s technique for his etchings, sketches, etc., with an increasingly mathematical – if quirky – aesthetic, which he applied to “recognizable” subjects, such as birds and fish, that seemed to have no beginning or end. The Dutchman was also “smitten by the music” of Bach, impressed by the rhythmic structures of the Baroque compositions. To paraphrase Shakespeare, there was indeed “a method to [Escher’s] madness.”

Despite leaving Italy, as fascism spread throughout Europe, Nazi occupation inevitably caught up with and impacted the Escher family, which had settled in Belgium. One of his sons notes onscreen, “he couldn’t travel, in his studio he wanted to create. He created his greatest works during this period.”

As he progressed with his engravings, etchings, etc., at one point Escher mused, “Maybe I’m not so far removed from Einstein’s curved universe.” In fact, I’d say that as far as M.C. Escher’s imagery goes this artistic genius gives a whole new meaning to Einstein’s famous formulation that “E=MC2”.

The Dutchman, who lived until 1972, comes across a bit curmudgeonly and ungrateful. He attained his greatest popularity during the counterculture’s heyday, but eschews his most ardent admirers and their adulation. “What on Earth do these young people see” in his art? he pondered. He blows Mick Jagger off when the Rolling Stone asks him to design an album cover. Nevertheless, after Eric Burdon of the Animals introduces Graham Nash to Escher’s art, the Crosby, Stills and Nash musician declares: “It changed my life.”

For some reason Journey doesn’t state the obvious reason why the Flower Power generation was so drawn to Escher’s drawing, prints, etching, engravings, etc.: Because his mind-blowing work had a psychedelic sensibility that altered one’s perception of reality. This despite the fact that Escher wasn’t much of a colorist, sticking to more somber tones of blacks, grays, browns. Of course, this didn’t stop Acid-inspired hippies from adding what a bemused (if not irritated) Escher derided as “fluorescent ink, ultra-violet light, shrill colors” to poster versions of his oeuvre. Like it or not, the counterculture’s merry pranksters were attracted to what the Dutch artiste described as “A mishmash that lacks all profoundness – a child’s game.” Experiencing mind-expanding trips, they could relate to this talent and his singular journey that changed what and the way we saw.

At one point, as Stephen Fry gives voice to Escher’s reflections, the pensive virtuoso speculated about making a “film.” I like to think that in doing so, M.C. would have given Walt Disney a run for his money, and the production may have looked something like Robin Lutz’s Escherian biopic. Whether you are an art historian, expert or layman, dropping LSD or stone cold sober, this highly entertaining, innovative 81-minute tour de force is, like its subject’s imagery, simply a joy to behold. When it comes to filmmaking, Lutz is no klutz. Enjoy the unraveling, from here to eternity and beyond!

Starting Feb. 5, to see M.C. Escher: Journey to Infinity go to Kino Marquee – and prepare to blast off!